Appellants today are experiencing a double whammy of sorts. Whammy number one is they are being hit with larger and larger judgments than in the past.

According to a study published in 2022 by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce Institute for Legal Reform, “The median reported nuclear verdict increased from $19.3 million in 2010 to $24.6 million in 2019. This represents a 27.5% cumulative increase in the median nuclear verdict over a 10-year period which inflation rose by 17.2%.” The median nuclear verdict has likely increased even further over the past 6 years since the most recent study was published.

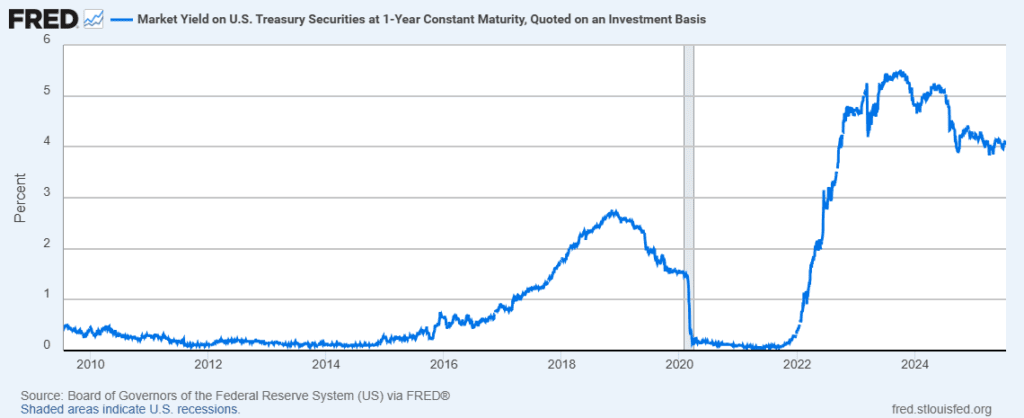

The second whammy comes from higher interest rates. Many jurisdictions require the appeal bond to cover interest and costs during the appeal, and during 2009 to 2019, appellants benefited from historically low interest rates. However, that changed when the Federal Reserve increased interest rates significantly starting in 2022.

Using the federal rate as required in many federal district courts as a proxy and assuming it takes two years for an appeal to conclude, appellants in certain jurisdictions are having to obtain appeal bonds for roughly 4% to 8% more than they were in the prior decade.

State Appeal Bond Caps

According to a University of Pennsylvania Law Review article published in 2014, forty-one states have passed some sort of appeal bond reform statute since 2000 many of which explicitly place limits on the amount of the appeal bond required by an appellant. These efforts took place as part of overall tort reform in many states in reaction to the very large verdicts resulting from the tobacco litigation in the 1990’s, the Texaco Inc. v. Pennzoil Co. case, and others. The purpose of the bond caps is to preserve the appellant’s rights to appeal if they don’t have sufficient collateral to obtain the bond or it would be so detrimental to their financial standing that it could jeopardize their viability as a going concern.

Some states like Texas, Georgia, Hawaii, and Virginia simply cap the dollar amount required, and each of these states have currently set the maximum bond amount at $25 million. Based on our research, those states that have caps typically range between $25 million to $150 million.

Several states have carveouts for small businesses such as the $1 million bond limit in Nevada or limitations or exemptions for Master Settlement Agreements. Other states like Nebraska and Texas rules limiting the appeal bond to 50% of the appellant’s net worth.

Due to the higher verdicts and interest rates, we are seeing more bonds hit these caps than we did in the past, which is helping to limit the size bond that some appellants would otherwise be required to obtain. To that end, it can be said that appeal bond caps are serving their intended purpose of preserving an appellant’s right to appeal.

There is a counter argument to appeal bond caps in that they limit the financial protection of the judgment creditor to an amount less than the judgment, so the judgment creditor is in essence not fully secured. Furthermore, many appeal bond caps simply limit the amount of the bond required regardless of the financial ability of the appellant to obtain the bond.

The complete arguments for and against appeal bond caps are beyond the scope of this article, but we do think all states would benefit from having some sort of cap relating to the financial ability or net worth of the appellant to obtain the bond, because that form of cap benefits both the judgment debtor and creditor. The judgment debtor preserves their right to appeal, and if it is a corporate defendant, their viability as a going concern. The judgment creditor benefits from getting some financial protection instead of nothing if no security is provided or the judgment debtor is forced into bankruptcy.

This cap may come in the form of a combination of the following:

- Determining the maximum amount that a surety company would provide a bond for based on the collateral the judgment debtor can provide;

- The court’s discretion based on the judgment debtor’s ability to provide the collateral and remain solvent.

Simply limiting the bond amount to a percentage of the judgment debtor’s net worth can be problematic in that it doesn’t take into account whether a surety company would be able to provide a bond for the equivalent percentage of their stated net worth. Sureties often discount the value of certain assets or they may not be willing to use certain assets as collateral, and therefore, the bond amount a surety could provide may be less.

Impact of Larger Bond Requirements

Caps on appeal bonds only help in those states that have them and only for judgments that actually hit the cap. As a result, it can be harder for some appellants to qualify for the larger appeal bonds both with and without collateral. Let’s take a look at both situations.

Uncollateralized Bonds

When a surety company considers providing a bond on an uncollateralized basis, they review the financial strength of the appellant relative to the bond size required. Therefore, if someone needs a $10 million appeal bond instead of $5 million, the requirements are going to be greater for the higher amount.

While there are no set ratios, because a variety of factors are considered, the surety is generally looking for the appellant to have cash, liquid resources, and available credit lines of 10 to 20 times that of the bond required to demonstrate that they will be able to easily satisfy the judgment on their own in 2 to 3 years when the appeal is finally concluded.

Larger bonds obviously make this more difficult, and this is particularly true for smaller to mid-sized businesses. As a result, we are seeing some appellants who may have qualified for uncollateralized bonds in the past be required to put up collateral

Collateralized Bonds

If a surety company cannot qualify the appellant for the bond based on their financial strength, then the surety will require collateral. The collateral typically has to be in the full amount of the bond. While there are some limited exceptions, roughly 95% of bonds are either written without any collateral or collateral in the full amount of the bond. Larger judgments and ultimately, larger appeal bond requirements have made it more difficult for some appellants to have enough collateral available to fully secure the bond.

Alternative Solutions

We have seen a few courts allow for smaller bond amounts even when there is not a statutory cap in place. There have also been instances where the parties have been able to stipulate to a lower bond amount than the rules require. Often the judgment creditor is incentivized to take something rather than nothing.

In both instances, the judgment debtor typically has to demonstrate their inability to obtain the bond for the full amount, and we are often asked to provide affidavits in these situations confirming this to be the case.

Conclusion

The dual pressures of rising verdict sizes and higher interest rates are reshaping the appeal bond landscape. While state-imposed caps and alternative solutions offer some relief, they are far from universal. Appellants must proactively plan for the financial demands of an appeal, including early evaluation before a judgment is entered and discussion of the potential collateral requirements. Defense and appellate council are on the front lines of this and in the best position to advise their clients to take these steps early.